Community resources

Community resources

Community resources

Control Chart vs Real Workflow Time: What Jira Shows, What It Hides

Picture this: you open Jira’s Control Chart, see the rolling average trending down, and think, “Nice — we’re getting faster.”

Then someone from Support (or your most patient customer) asks the worst possible question:

“Cool. Why do my tickets still take forever?”

Both can be true — because Jira’s Control Chart is not lying… it’s summarizing. And when you summarize messy reality into one number, the most important details are often the first to disappear.

This article breaks down:

- what Jira’s Control Chart really measures (and how),

- the most common ways it misleads teams, and

- how Time in Status makes cycle time reflect your actual workflow — without turning metrics into fiction.

Jira Control Chart: what it is (and what those dots actually mean)

Atlassian describes the Control Chart like this: it takes the time spent by each work item in a particular status (or statuses) and maps it over a selected period. It shows average, rolling average, and standard deviation to help you judge predictability.

- It’s a scatter plot of completed (or selected) items.

- Each dot is a work item (or a cluster of work items).

- The chart is built to answer: “How long did items take (as Jira defines it), and is that time stable enough to forecast?”

The two metrics: cycle time vs lead time (Jira’s definitions)

Jira explicitly distinguishes the two:

- Cycle time = time spent “working on” a work item, typically from when work begins to when it’s completed — and if the item is reopened and completed again, that extra time is added.

- Lead time = from when a work item is logged to when it’s completed.

That “reopened time is added” clause matters more than most teams realize. If you reopen often, Jira’s cycle time becomes a blended metric: delivery time + rework loops.

How Jira Control Chart calculates cycle time (the part people skip)

Step A: you select the statuses (Jira calls them “Columns” in the report UI)

Cycle time is determined by the statuses you include in the report. Jira tries to auto-select “work” statuses, but Atlassian is very clear: you should configure it to include the statuses that represent time spent working.

Example from Atlassian:

- Work starts at In Progress

- Work completes when it transitions from In Review → Done. So you’d select In Progress and In Review to see time spent in those statuses.

Jira’s cycle time is not “one universal truth.” It’s “time spent in the statuses you told me count.”

Step B: each dot’s X-axis is when the item left the last selected status

This is a sneaky detail that changes how you interpret trends.

Atlassian states the horizontal placement indicates when the work item transitioned out of the last status selected (or most recently transitioned out of one of the selected statuses, depending on configuration).

So if you choose In Progress + In Review, the dot’s date is tied to when the item moved out of the “last” of those statuses — not necessarily when it was released, shipped, or actually delivered to a customer.

Step C: the rolling average is work-based, not time-based

The rolling average line is computed using 20% of the total work items displayed (odd number, minimum 5), centered around each item. It’s not a “last 7 days average.”

Why this matters:

- If throughput changes (you finish more items), your rolling average behavior changes even if the process doesn’t.

- It’s useful, but it’s easy to misread as a simple time-window trend.

Step D: the blue band is standard deviation (aka “how predictable are we?”)

The shaded band is standard deviation around the rolling average. Narrow band = more predictability, wider band = chaos (or a mixed dataset).

Bonus nuance: the Y-axis scale can change

Jira may switch the elapsed-time axis scale (linear vs cube-root power) depending on timeframe and outliers. If someone screenshots two different timeframes and compares “shape,” you can accidentally compare apples to distorted apples.

What Jira Control Chart shows well

Control Chart is genuinely good at:

- spotting outliers worth investigating

- seeing whether variance is shrinking (predictability improving)

- showing whether a process change might have shifted the system

It’s a diagnostic chart, not a scoreboard.

What Jira Control Chart hides (where “misleading cycle time” is born)

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: The Control Chart can’t tell you why cycle time is high

It can show “this item took 12 days,” but it can’t answer:

- Was it 12 days of active work?

- Or 30 minutes of work + 11.5 days waiting for review?

- Or blocked by another team?

- Or waiting for customer input?

- Or stuck because no one noticed it?

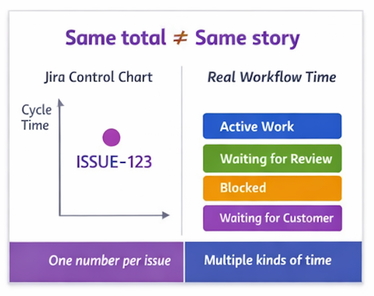

It’s one number per item — and real workflow time is usually a stack of different kinds of time.

“Working days” still don’t automatically mean your working reality

Jira boards have configurable working days, non-working days, and timezone, and Atlassian notes these settings affect Control Chart and other reports.

But in practice, teams still get tripped up because:

- some teams want business hours, some want calendar time,

- distributed teams don’t share one timezone reality,

- and “days/weeks” display conventions can confuse stakeholders (even when calculations are adjusted).

It’s sensitive to workflow design quirks

If your workflow includes:

- a catch-all status like “In Progress” that actually includes waiting, review, blocked, QA, etc.,

- or “Done” that really means “Dev done but not deployed,”

then the chart is still “correct” — but the metric is now measuring your workflow ambiguity, not flow.

It can include things you didn’t mean to measure

Atlassian literally provides tips for removing misleading data points:

- filter invalid outliers (e.g., something left in progress then dropped back)

- exclude “triage casualties” (duplicates, won’t fix, answered, etc.) because they skew cycle time downward

- exclude current work if you only want completed items

If a report needs three official “how not to accidentally lie” tips, that’s a hint: your configuration choices matter more than the chart UI suggests.

The classic mistakes teams make with Jira Control Chart

If you want an “Explainer + mistakes” checklist, start here:

- Letting Jira auto-pick statuses and assuming that matches reality

- Using average as the headline number (instead of percentile/median)

- Mixing issue types (bugs + epics + requests) and calling it “team cycle time”

- Including “Done” statuses that aren’t truly “done”

- Measuring cycle time while ignoring waiting time % (the silent killer)

- Treating the chart as a KPI to “hit,” which incentivizes workflow gaming

- Comparing teams with different workflows like the numbers are comparable

- Forgetting that reopened work adds time (Jira does that by definition)

Real workflow timing needs two things Jira Control Chart doesn’t prioritize

To make cycle time match real work, you need:

- A) A definition that matches your value stream. “Cycle time” is only useful when the team agrees on:

- start event (first meaningful work? first commit? first “in progress”?)

- end event (done in Jira? deployed? accepted? released?)

- whether waiting states count as part of cycle time or are tracked separately

- B) A breakdown of time, not just a total. Most improvements come from reducing:

- wait states (review queues, blocked states, “Waiting for customer”)

- handoff delays

- WIP overload

You can’t improve what you can’t see. That’s where Time in Status comes in.

Time in Status: what it adds on top of Jira

Time in Status is designed to turn Jira’s status history into actionable time-based metrics — not just one dot per ticket.

The key idea: you don’t only get “how long,” you get “where”

Instead of compressing workflow time into a single elapsed value, you can look at:

- time in each status

- grouped “logical” phases (active work vs waiting)

- per-assignee timing

- trends and pivots by project/sprint/epic/type

The setup flow (what matters for cycle time accuracy)

When you create a report, you control five knobs that decide whether the metric is useful or misleading:

- Report type (time in status, average time, status count, etc.)

- Filters (assignee, project, sprint, JQL, epic…)

- Two date ranges:

- Work items period = selects which issues are included (created/updated/resolved in a period)

- Report period = trims the window for time calculations

If you don’t set report period, it calculates for the whole history (“Any date”).

- Work items period = selects which issues are included (created/updated/resolved in a period)

- Work schedule (24/7 vs custom working calendars)

- Status Groups (the heart of cycle time definition)

This “two-date” model is the difference between:

- “What did we finish last sprint, and how much time did it spend during the sprint?”

and - “What did we finish last sprint, but how long did it take across its full history?”

Those are not the same question — and mixing them is one of the most common causes of cycle-time confusion.

How cycle time is calculated in Time in Status

Time in Status treats cycle time as a sum of time intervals spent in selected statuses — exactly the way your workflow actually unfolds.

The mental model

Every issue has a timeline like:

Status A → Status B → Status C → … (with timestamps)

Time in Status reconstructs that timeline and calculates durations:

- per status

- per group of statuses

- within the selected report period window

- using either 24/7 or your working schedule calendar

Cycle time = time in a “Cycle Time” status group

You define a status group that represents your delivery phase, for example:

- In Progress

- In Review

- Testing

- Ready for Release

Then the cycle time metric is the total time spent in those statuses (and yes, if an item goes back and forth, it will count the time across those transitions — which is exactly what you want if you’re measuring real flow and rework).

This directly solves the “one number hides everything” problem because you can also create complementary groups:

- Active time group (hands-on statuses only)

- Waiting time group (blocked, waiting for review, waiting for customer)

- Lead time group (everything except final done)

Now you don’t have to argue whether cycle time “should include waiting.” You can track both and stop fighting about semantics.

A concrete example: how Jira can look better while reality gets worse

Let’s say a team “improves” cycle time by changing their workflow:

- Before: In Progress → In Review → Done

- After: they add Waiting for Review but still select only In Progress + In Review on Control Chart.

What happens?

- The item sits 3 days in “Waiting for Review”

- Control Chart doesn’t include that status (because you didn’t select it)

- Cycle time appears lower

- Customers still wait longer

- Everyone loses trust in metrics

With Time in Status:

- You’d see “Waiting for Review” balloon immediately.

- Your “waiting time %” spikes.

- You can fix the system (WIP limits, review SLA, swarming), not just the chart.

Quick comparison: when to use which

|

Need |

Jira Control Chart |

|

|

Quick view of cycle/lead time distribution |

✅ |

✅ |

|

Predictability signal (variance) |

✅ (standard deviation band) |

✅ |

|

Explain where time is spent (queues vs work) |

❌ |

✅ |

|

Define multiple “cycle times” for different value streams |

Limited |

✅ (status groups + filters) |

|

Business-hours calendars vs 24/7 |

Board working days exist |

✅ (24/7 or custom schedules) |

|

Slice by sprint + trim calculation window |

Limited |

✅ (work items period + report period) |

How to avoid misleading cycle time (a playbook you can actually run)

If you want cycle time metrics that survive skeptical stakeholders and messy workflows, do this:

Step 1: Define 3 metrics, not 1

- Lead time (request → done)

- Cycle time (work start → done)

- Waiting time % (waiting / total), or at least “time in review / total”

A single metric invites storytelling. A trio invites understanding.

Step 2: Make statuses earn their meaning

Kill “catch-all” statuses. Every status should answer:

- “What state is it in?”

- “Who owns the next action?”

- “What’s the exit criterion?”

If you can’t answer those, you can’t measure flow.

Step 3: Separate selection from calculation

- Select which work items matter (e.g., “resolved last sprint”)

- Then decide the time window you’re analyzing (e.g., “time spent during sprint dates”)

That’s exactly what the Work items period vs Report period split is designed for.

Step 4: Investigate outliers like a detective, not a judge

Outliers are almost always a process story:

- unclear DoD,

- dependencies,

- review bottlenecks,

- WIP overload,

- blocked work no one escalated.

Atlassian even recommends filtering invalid outliers and triage casualties to keep data meaningful.

Closing thought

Jira’s Control Chart is a great instrument — but it’s closer to a thermometer than an MRI. It tells you “something’s off” (or improving), but it doesn’t show where the problem lives.

If you want cycle time that matches reality:

- define the workflow truth (statuses + meaning),

- measure time by phase (active vs waiting),

- and make sure your date range matches your question.

Was this helpful?

Thanks!

Iryna Komarnitska_SaaSJet_

0 comments