Community resources

Community resources

Community resources

What to Do: The Difficult Art of Decision-Making

We all make decisions all the time. Car or public transport? Ham & cheese, or tuna & cucumber sandwich? Allocating resources from task 1 or task 2? The more people or teams we manage, the more work is based on choosing the most beneficial options, or in more dire scenarios, the least harmful ones.

Every day, an adult person makes up to 35,000 decisions. This number is significantly higher when one supervises teams and other people’s work. No wonder many management experts and consultants studied the patterns and steps that lead from initial thoughts to the measured response. Let’s take a look at the big one – Peter Drucker, the guru of consulting, and David Bowie of the management world, how he described the 6-steps approach for decision-making:

The first 3 steps will help us determine the frame we move within. Classifying the problem helps us understand if we deal with a new kind of challenge, or is it a more generic one. Defining and naming it helps us understand what exactly we are dealing with. Specifying the answer will narrow the possible solutions.

The latter three steps are meant to maximize the positive outcome of the whole process. Deciding what “right” options are the best solutions. The next step is the commitment into action, assigning it, and taking responsibility. As Drucker wrote, without commitment, the decision is only a good intention. The final one is feedback, based on information from monitoring and reporting the whole process. No matter what, the final decision can still be a wrong one. This point helps us understand if we made proper assumptions, or based them on obsolete information and processes.

Naturally, this is one of many approaches we can find online. However, most of them consist of a similar number of steps that focus on pointing out the issue, addressing the methods to approach it, delegating responsibility, and assessing the outcomes. This is the most straightforward approach for decision-making, which may save us a lot of time, and put our resources and work power into the best possible use.

The tangled world of Project Portfolio Management

Narrowing down the decision process to the PPM world, we must understand the PPM Manager work specifics. Ben Almojuela from Boeing Commercial Airplanes presents an on-point definition. He sees portfolio management as a dynamic decision process, whereas a set of active new products and projects is regularly evaluated, prioritized, and selected. The main goal is to obtain the greatest possible value from limited resources. With this definition, portfolio management can be described by six factors: project evaluation, resource allocation across projects, resource allocation, strategizing, project prioritization, and project selection. Yet, another element, very often omitted appears in basically every mentioned step – risk management. Every manager must assess and point out potential threats to the workflow, no matter what methodology he works with.

Why is risk management so important? Seems pretty obvious, as it helps the company to consider and point out various potential risks and threats, predict what may go wrong, and effectively prepare for unforeseen obstacles. The well-prepared plan helps the company establish procedures to avoid potential threats, minimize their impact and cope with their results. There are far more benefits, such as increased stability of companys’ business, lessening the legal liability, and a safer environment for people involved.

Unfortunately, some PPM managers treat risk management more like a burden. They don’t assess potential threats properly or do it just to meet the procedures. But how can one effectively prepare for potential bumps on the road?

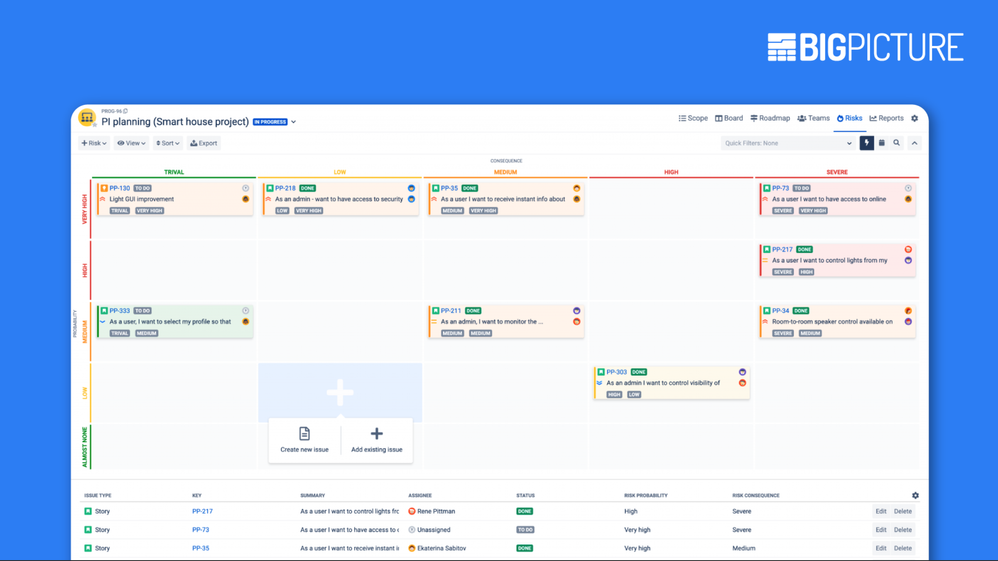

A very special tool

The risk register is a very beneficial tool here. It is a repository for all identified risks that includes additional information about each risk, like its nature, personal responsibility, and possible course of action. It sounds helpful, but most managers do not use the risk register in their work, as much as they should. They often copy it from different projects to meet the methodological requirements, and later they forget about it. And when risks materialize, such as delay in schedule or sudden change in the budget, managers act ad hoc, as they’ve decided to skip theoretical preparations. Effectively, they fight with results, not causes.

The first step is to change the attitude to the risk register. Importantly, adding it to the workflow doesn’t cross with other methodologies. The risk register can be helpful within classic, Agile, and hybrid methods. Managers don’t have to obey every rule of each methodology. However, they must know their basics to search and find the components that suit them and their teams’ needs in the most suitable way.

Knowing the theory is one thing, but using it in practice is another. The good manager learns by doing and especially from their own mistakes. The ability to retrospect, analyze the failure step by step, and admit to it is one of the critical competencies. This last element is essential for good leadership. It builds trust and better relations with the team and serves as a tool for building authority. On the other hand, dismissing or blaming someone is a way to demoralize and dismiss the team quickly, as members will feel they do not have the support of their manager. The same goes for micromanagement. Treating team members like children and leaving no space or autonomy is also a wrong decision.

A good manager is a person that knows how to work and motivate their employees, has a good knowledge of different methodologies, and can follow their gut. Some things cannot be taught and learned. A pinch of talent can sometimes decide if someone will be a great or just an average leader. However, even the most talented people must have some basic knowledge and choose proper tools to use their potential to the fullest.

Author: GRZEGORZ BURTAN

Was this helpful?

Thanks!

Anna-BigPicture

About this author

Project Manager

Appfire

Poland

104 accepted answers

Atlassian Community Events

- FAQ

- Community Guidelines

- About

- Privacy policy

- Notice at Collection

- Terms of use

- © 2024 Atlassian

0 comments