Community resources

Community resources

Icarus Labs research diary: Hiding malware in Docker Desktop's virtual machine

If you'd rather skip straight to the technical details, here's the blog post explaining how it all works.

This post is the high-level story of how this technique was found, in which the story makes the thrilling transition to first-person.

First things first: If you’re reading this, we somehow got away with calling it “Icarus Labs”.

I’m writing this because I realised the techniques for how we do research are sometimes just as valuable as the research itself.

But that’s me saying this now, on the other side of my mad scientist moment. The time has now come for a gratuitous and ultimately superfluous flashback to how it all started....

Playing hide-and-seek on someone’s computer for a long time

Okay I think the flashback is working.

One day, my teammate asked me what I thought it would take to hack a computer, and then keep it hacked for a long time, like a year.

The goal was to install malware, and keep it there. By "malware", I mean "remote access software": You can control their computer from your computer. This is what attackers want because they can download secret files, turn things on and off, and generally do anything you can do with your computer.

A year is.... a long time to hide on someone else's computer, by my standards. We'd need to make sure that the malware didn't obviously stand out, make sure it didn't crash the user's computer, and make sure it didn't get removed when the computer was rebooted, or had a system update.

I was thinking we probably weren't going to get away with using a technique for hiding that anyone could just Google. What if, during that year, someone decided to just... check in all the common hiding places? Those kind of rare events become much more likely if they have a whole year to happen.

So, I realised my best shot was to try and find a new way of hiding, that nobody's seen before. It's hard to find something if you don't know what it looks like.

Hmmm, where should I look for a new technique?

The ways of persisting (keeping your malware running, even if the computer restarts/updates/etc.) on macOS that I knew about were pretty basic. The current state of the art is to use a LaunchAgent (the macOS equivalent of a cronjob/recurring task) to automatically run your malware whenever the computer starts up.

I realised everyone's trying to persist on macOS, so it's hard to find something that nobody has tried yet. But, people's computers don't actually run plain, fresh macOS, like they're straight out of the Apple store. They install all this extra stuff to get work done, especially if they're software developers. Why, they often install, at a minimum, things like Homebrew, Docker, iTerm2 etc.. These apps have much less security review than macOS itself, and are developer tools, so even more likely to trade off security for more powerful features.

There are many legit apps that want to do the task: “run a program, and keep it running”. I was hoping to find a way to use one of these apps in a legitimate way (i.e. not by finding and exploiting a bug) because, well, it’s already a feature. If I were an attacker, just hypothetically, I’d love for my persistence method to be a legit feature, since it would blend in nicely, and be less likely than a bug to be removed in a future update.

It seemed like the best place to persist would be in some specific software/configuration of the machine, rather than in the OS itself. Of course, this is a flexibility tradeoff: You don't know what software is going to be on the target machine when you get to it, so you can't guarantee that your method will work in advance. We make this tradeoff with operating systems all the time (e.g. preparing malware that only runs on Windows, or only on Linux), so I decided to try and trade off even more flexibility for a better persistence method.

Which software seems like a good target?

"What's some software that every developer has on macOS?", I thought. Ah, Docker, Homebrew, maybe VSCode, or iTerm2? Which of those sound like they'd be good places to hide malware? Well, which of them execute code? Actually, all of them execute code, and all of them sound like pretty good places to hide to me. But, I tried Docker first, because I knew it had a lot of features, could access the whole machine, open ports, and seemed just a little too difficult to use in a safe enough way.

The bottom line

Anyway, this has been a rambly way of dancing around the fact that I ultimately stumbled on this techique by Googling "docker docs" and Cmd+F'ing the page for "exec".

Part 1: Stumbling upon my new best friend, runc

But first: what is Docker?

Docker lets you run someone else's code on your computer. But, when someone gives you their code to run, they also give you the exact setup they use to run it (a container). This fixes the "well, the code works on my machine" problem, since now you and the other person are running the code on the same machine: the Docker container they made and sent to you.

I wanted to know if Docker could be told to execute code regularly, because that sounds a lot like persistence to me.

My new best friend

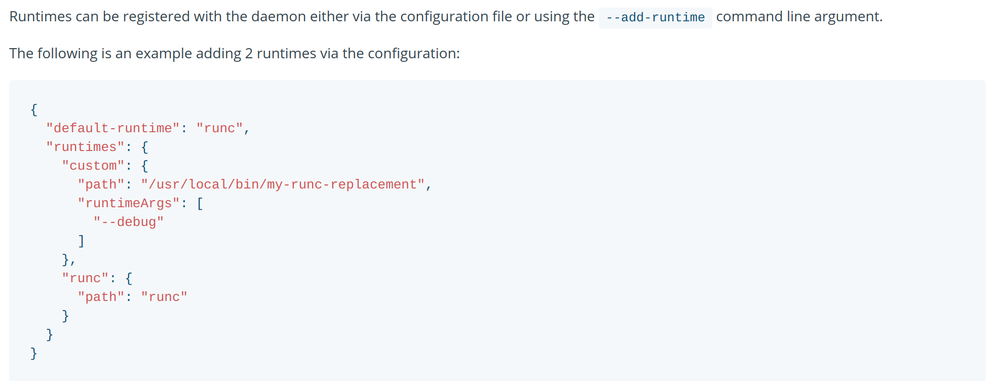

When I was searching the Docker documentation for ways to execute code, I had no idea what I was looking at. There were "runtime execution options". I like execution? But what exactly was this page telling me could be executed? By who? Where? I didn't know. But, I did know I could specify a binary to run whenever a Docker container was run.

Uncanny. That looks almost exactly like I can put a path to a binary in this config file, and Docker will run the binary.

Running a different binary in place of runc

Surely I can just point the config file above at my malware binary and call it a day. At first, I did that, and instantly broke my Docker to the point where it was unusable. It turned out this "runtime" binary actually did something, and the malware I was replacing it with did not so much “do that thing” as “be malware”. So, I tried to find a way to modify the real binary so it did whatever it's supposed to do and also runs my malware.

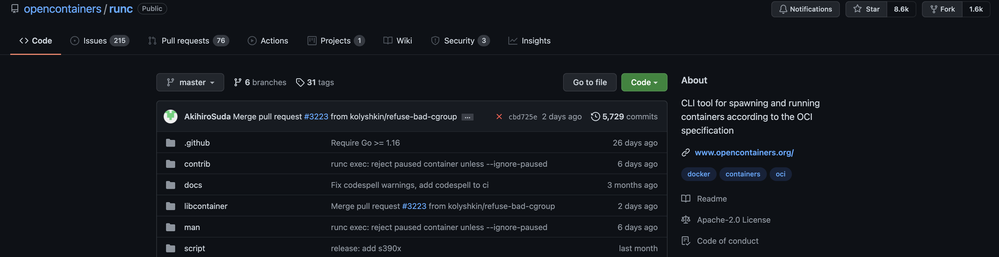

I found out that the default "runtime" was something called runc, and that it's on Github.

Oh. Well, if I have the source code for the actual, real binary Docker uses to run containers, then.... surely nobody will notice if I make some adjustments to it 👀

I modified the source code of runc to also download and execute my malware, recompiled it, and then told Docker to use my new runc-but-worse binary.

Testing it out

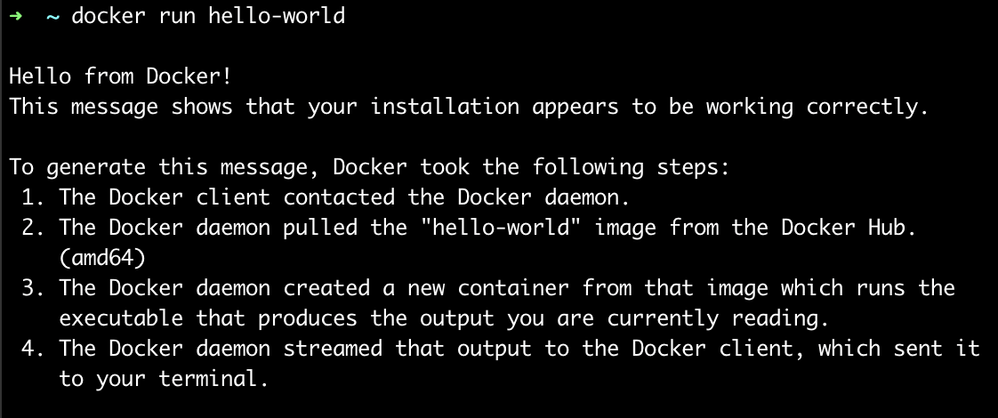

I tested it out by running docker run hello-world, here’s a lil' comparison.

Original runc:

With runc-but-worse:

:))

The only difference was that when I used runc-but-worse, I also saw that my malware had registered a new connection.

It was then that I thought "wait that actually worked 🧐", and went back to my teammate and said "hey I think I might have found something that would keep you hidden for a year".

I didn’t even know about the virtual machine at this point, I was just happy to have Docker executing my code. When I realised the code wasn’t running on my laptop, I figured it was running in a Docker container maybe? Only when I realised it was actually running in a Docker container inside a virtual machine did I realise how much trouble I’d got into.

Part 2: The struggle

That was the first few days. The rest of the 3-month research block was figuring out exactly how much access my malware had, trying to get more access, refining the technique to be stealthier, and trying a truly tremendous amount of things that didn't work.

A couple of times, I'd do a demo for my team, showing them what I'd been able to do so far, and desperately seeking validation on whether this was actually useful or whether I'd become delusional. I'd ask them to give me even more demands. "Tell me why this is bad, and what it's missing", I'd say. Seeing what they wanted out of a technique like this gave me lots of ideas for new things to try and make it do, and some of them worked!

I also asked Atlassian's Security Intelligence Team for help. They're the team responsible for detecting and responding to degenerate hackers like me, and they helped test out how hard it would be to detect whether someone had used this technique.

Eventually, I got the technique to a point where I was happy enough with publishing it (my 3 months was running out), and here we are.

Things that didn't work

-

Trying to escape the Docker container the malware starts in, only to realise that escaping would just escape into... one layer higher, the Virtual Machine, not the user's actual Mac.

-

The time I swan-dove down the rabbit hole of macOS app updates using Sparkle, in an attempt to backdoor Docker Desktop updates after they were downloaded but before they were installed

-

A truly tragic number of things that are not even interesting enough to mention here

What I learned

-

Having a precise goal helps you know what to do next, since you at least know what you're trying to do

-

When you have an idea for what might work, test whether it works as quickly as possible

-

Record/log/write down what you've tested before, so you don't duplicate work

-

You can also analyse it later and try to divine wise conclusions from it

-

-

People really wanted to run Docker on macOS, even though it only works on Linux, to the point where the best solution was to run an entire Linux virtual machine just to run Docker

-

Reverse engineering how something works is slower, because you have to test your theories, and most of them end up being wrong. Where there was documentation available, it saved a lot of time

Wait, but I desperately wish to know all the technical details of how it works!

Convenient because here is a blog post explaining the technique in scholarly detail.

Was this helpful?

Thanks!

Alex Hope

TAGS

Atlassian Community Events

- FAQ

- Community Guidelines

- About

- Privacy policy

- Notice at Collection

- Terms of use

- © 2024 Atlassian

1 comment